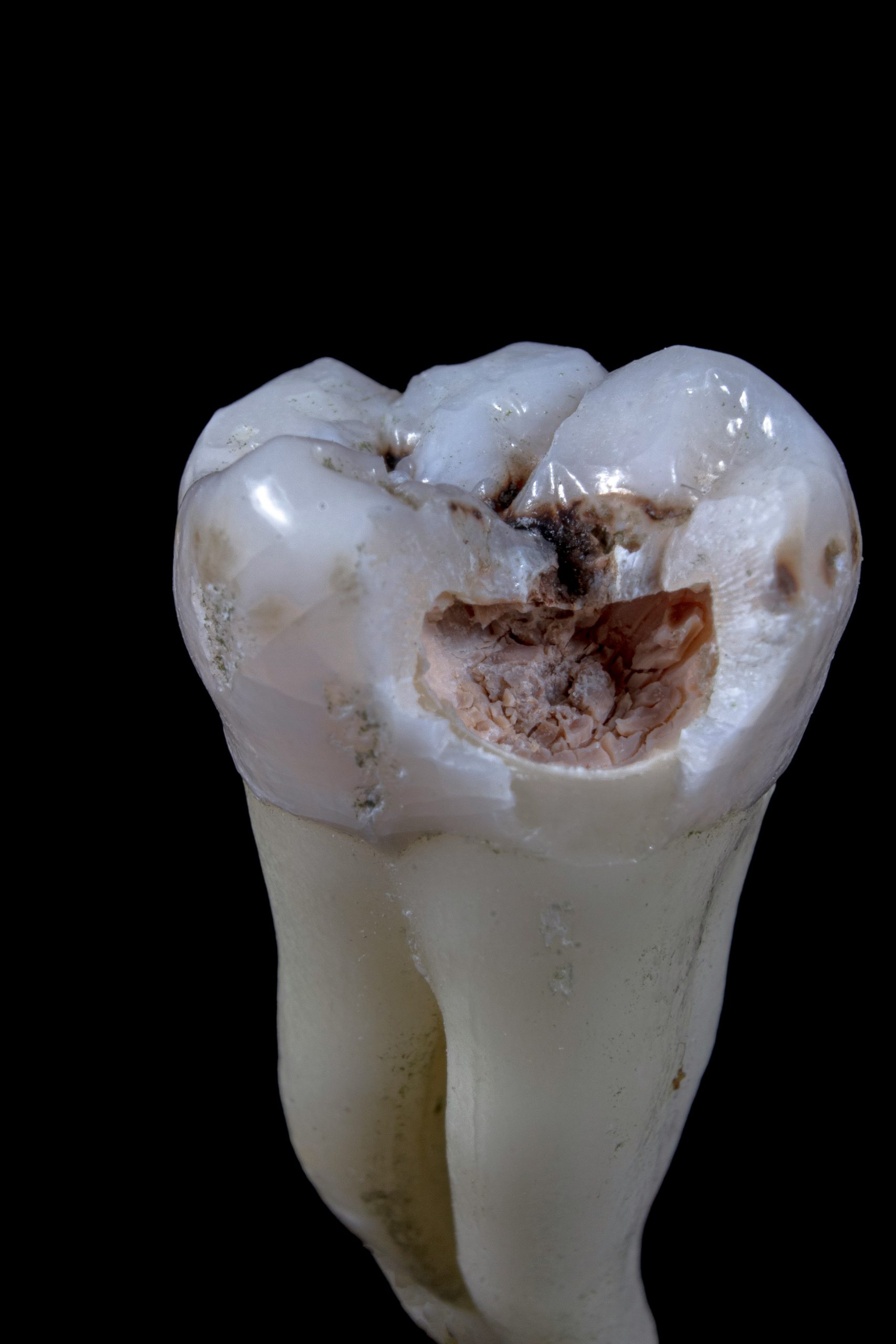

Third molars, also known as wisdom teeth, are the last to erupt between the ages of 17 and 26 years, which complement the functioning of the second molars (Kruger et al., 2001). They fail to erupt entirely in approximately 24% of the population and are observed to be associated with periodontal defects and caries on adjacent molars (Carter & Worthington, 2015; Shugars et al., 2005). It is also observed that the associated pathology may be sometimes asymptomatic, with certain reports recommending its removal even before its eruption in all young adults (Ash, 1964; White & Proffit, 2011). This makes third molar extraction one of the most frequently performed dentistry procedures by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. However, removing the asymptomatic third molars is highly debatable as there is limited data on the prevalence of third molar pathology specifically among asymptomatic individuals (Eke et al., 2010). A recent study employing 409 healthy young adults (average age: 25 years), showed periodontal pathology with a probing depth>4mm (PD4+) in 65% of individuals with four asymptomatic third molars (Garaas et al., 2012). Another longitudinal study showed an increased risk of developing additional PD4+, in the presence of pre-existing PD4+ (White et al., 2008). It has also been suggested visible mandibular third molars may be a greater risk due to provision of a greater and deeper biofilm gingival surface, which are more conducive for anaerobic inflammation (Offenbacher et al., 2007; Rantanen, 1967).

In recent times, it has also been suggested to perform the third molar extraction, only if there is compelling evidence that it is indispensable due to surgery associated pain and complications, adverse impact on health-related quality of life and economic burden (Duarte-Rodrigues et al., 2018). Several clear indications are well documented that demonstrate increased benefits to the patients compared to the risks involved. These include prevention or treatment of pericoronitis or caries or cysts and tumours, considerable unexplained pain, and association with bone-destroying pathology (Mello et al., 2019; Rajan et al., 2016). Additionally, as chronic oral inflammation is an established risk factor for renal and cardiovascular disease, orthodontic patients with heart valve disease or organ transplants should get their third molars removed. Despite the presence of one of the above conditions, a risk assessment is recommended based on age, body weight, and the existence of comorbid conditions, and the potential of risk damage to adjacent jaw structures. For instance, overweight patients often have large tongues and the existence of several metabolic diseases, both of which contribute to increased surgery-related complications (Marciani et al., 2004). Besides, old aged patients with atrophic mandibles are at increased risk of jaw fracture of poor recovery post-surgery (Sayed et al., 2019). Some precautions are also crucial for a surgeon to consider at the time of performing the surgery. These include judicious use of extraction force, the non-excessive opening of the mouth with props, and stabilization of mandibles when using forceps (Marciani, 2012). Nevertheless, certain postoperative responses are predictable, such as pain, swelling and difficulty in completely opening the jaws. Is it not uncommon for an orthodontic patient to show signs and symptoms of immediate nausea and vomiting, difficulty swallowing, and adverse effects of narcotic analgesics.

In summary, there is no need to remove every third molar and not every surgical procedure of removal of the third molar is similar. A poor surgical outcome may not be due to poor judgment or performance of the surgeon. There are clear indications for the removal of the symptomatic third molars. On the other hand, asymptomatic third molars may also contribute to significant morbidity due to the associated high diversity of microbes. Compared to a symptomatic patient, advising an asymptomatic patient is more challenging, as longitudinal studies have suggested PD+ develops later in life, specifically in those with late erupting third molars (Phillips et al., 2007). A routine clinical and radiographic evaluations may be necessary for the lifetime in such individuals (White et al., 2008). In the absence of sufficient evidence, a shared decision should be made with the orthodontic patient informing him about the possible risk of long term complications of both retaining as well as surgical extraction of third molars (Iwanaga et al., 2021). A recent report further showed that more than half of the asymptomatic and non-pathological 249 young adults opted for surgical extraction after being informed by the clinicians (Kinard & Dodson, 2010). However, to date, there is limited epidemiological evidence favouring the removal of asymptomatic third molars due to the absence of well-designed long term prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Ghaeminia et al., 2020).

References

Ash, M. (1964). Ash MM. Third molars as periodontal problems. Dent Clin North Am, 51.

Carter, K., & Worthington, S. (2015). Morphologic and Demographic Predictors of Third Molar Agenesis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res, 94(7), 886-894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034515581644

Duarte-Rodrigues, L., Miranda, E. F. P., Souza, T. O., de Paiva, H. N., Falci, S. G. M., & Galvão, E. L. (2018). Third molar removal and its impact on quality of life: systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res, 27(10), 2477-2489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1889-1

Eke, P. I., Thornton-Evans, G. O., Wei, L., Borgnakke, W. S., & Dye, B. A. (2010). Accuracy of NHANES periodontal examination protocols. J Dent Res, 89(11), 1208-1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510377793

Garaas, R. N., Fisher, E. L., Wilson, G. H., Phillips, C., Shugars, D. A., Blakey, G. H., Marciani, R. D., & White, R. P., Jr. (2012). Prevalence of third molars with caries experience or periodontal pathology in young adults. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 70(3), 507-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2011.07.016

Ghaeminia, H., Nienhuijs, M. E., Toedtling, V., Perry, J., Tummers, M., Hoppenreijs, T. J., Van der Sanden, W. J., & Mettes, T. G. (2020). Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 5(5), Cd003879. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub5

Iwanaga, J., Kunisada, Y., Masui, M., Obata, K., Takeshita, Y., Sato, K., Kikuta, S., Abe, Y., Matsushita, Y., Kusukawa, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Ibaragi, S. (2021). Comprehensive review of lower third molar management: A guide for improved informed consent. Clin Anat, 34(2), 224-243. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23693

Kinard, B. E., & Dodson, T. B. (2010). Most patients with asymptomatic, disease-free third molars elect extraction over retention as their preferred treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 68(12), 2935-2942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.058

Kruger, E., Thomson, W. M., & Konthasinghe, P. (2001). Third molar outcomes from age 18 to 26: findings from a population-based New Zealand longitudinal study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 92(2), 150-155. https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2001.115461

Marciani, R. D. (2012). Complications of third molar surgery and their management. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 20(2), 233-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.003

Marciani, R. D., Raezer, B. F., & Marciani, H. L. (2004). Obesity and the practice of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 98(1), 10-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.026

Mello, F. W., Melo, G., Kammer, P. V., Speight, P. M., & Rivero, E. R. C. (2019). Prevalence of odontogenic cysts and tumors associated with impacted third molars: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg, 47(6), 996-1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2019.03.026

Offenbacher, S., Barros, S. P., Singer, R. E., Moss, K., Williams, R. C., & Beck, J. D. (2007). Periodontal disease at the biofilm-gingival interface. J Periodontol, 78(10), 1911-1925. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060465

Phillips, C., Norman, J., Jaskolka, M., Blakey, G. H., Haug, R. H., Offenbacher, S., & White, R. P., Jr. (2007). Changes over time in position and periodontal probing status of retained third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 65(10), 2011-2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.055

Rajan, R., Verma, D. K., Borle, R. M., & Yadav, A. (2016). Relationship between fracture of mandibular condyle and absence of unerupted mandibular third molar-a retrospective study. Oral Maxillofac Surg, 20(2), 191-194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-016-0548-3

Rantanen, A. (1967). The age of eruption of the third molar teeth. Acta Odontol Scand, 25, 64.

Sayed, N., Bakathir, A., Pasha, M., & Al-Sudairy, S. (2019). Complications of Third Molar Extraction: A retrospective study from a tertiary healthcare centre in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J, 19(3), e230-e235. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.2019.19.03.009

Shugars, D. A., Elter, J. R., Jacks, M. T., White, R. P., Phillips, C., Haug, R. H., & Blakey, G. H. (2005). Incidence of occlusal dental caries in asymptomatic third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 63(3), 341-346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2004.11.009

White, R. P., Jr., Phillips, C., Hull, D. J., Offenbacher, S., Blakey, G. H., & Haug, R. H. (2008). Risk markers for periodontal pathology over time in the third molar and non-third molar regions in young adults. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 66(4), 749-754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2007.11.009

White, R. P., Jr., & Proffit, W. R. (2011). Evaluation and management of asymptomatic third molars: Lack of symptoms does not equate to lack of pathology. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics, 140(1), 10-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.05.007

Leave a Reply