Background

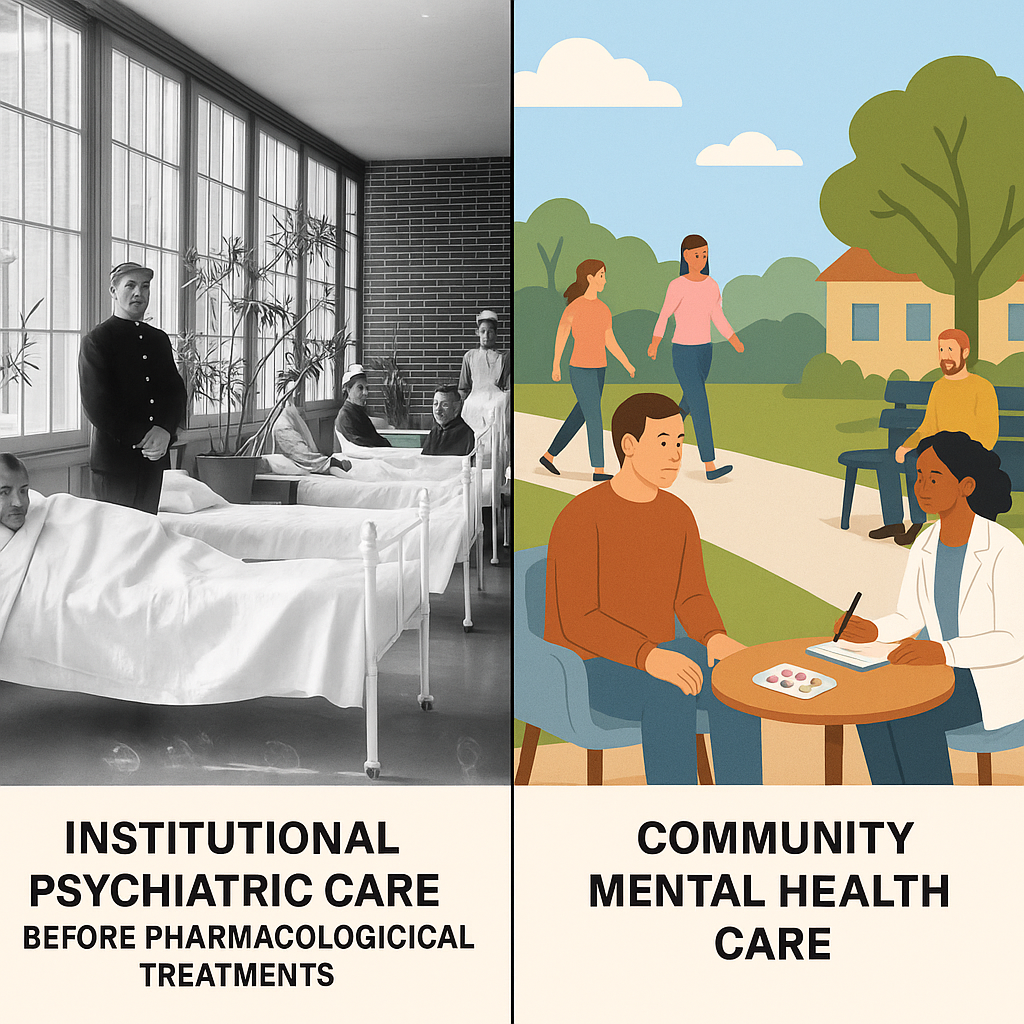

The form of care for the seriously mentally ill has undergone a significant transformation in the last century (Grob 1983). In the first half of the 20th century, state-sponsored institutes in mental hospitals were considered the primary providers for the long-term services and support for psychiatric patients (Arnhoff 1975). Such institutions accounted for almost half of all mentally ill patients, were considered as a symbol for a progressive nation that treated its mentally ill citizens well (Kramer 1977; Goldman, Adams, and Taube 1983). However, these institutions were often recognized as prison-like establishments where inmates were excluded from the outside world, often subjected to physical and social abuse, with a lack of contribution to society (Chow and Priebe 2013). Such institutions were under compulsion to accept all the mentally ill patients and thereby were unable to control the size of their population.

The objections to such a restricted environment for members of the society who had not committed any crime gained momentum in the form of civil rights movements in the 1950s, forcing policymakers to find an alternative mode of care and support for the seriously mentally ill. The following decades also witnessed advances in effective antipsychotic drugs, enabling policymakers to downsize psychiatric hospitals and establish mental health care in the community. This changing focus from hospital and nursing home-based services to home and community-based care came to be known as deinstitutionalization (Goffman 1961). The movement of deinstitutionalization soon spread across the whole world, and by the 1980s, less than 10% of all mentally ill patients were being supported exclusively in mental hospitals (Goldman, Adams, and Taube 1983; Kramer 1977). However, the effect of deinstitutionalization on the care of the mentally ill has been highly variable across countries due to differences in social welfare systems, cultural environment, and availability of resources at the community level (Becker and Vázquez-Barquero 2001; McCulloch, Muijen, and Harper 2000). Nevertheless, several studies thereafter demonstrated that discharged patients who received care in community-based settings lived a higher quality of life and gained community living skills (Segal and Moyles 1979). However, such studies also showed that there was no remarkable improvement in the clinical state of mentally ill patients (Priebe et al. 2002).

The objective of the study

The mental hospitals continue to be recognized as main care centres for individuals with acute mental illness who lack support, and there has been renewed investment in intuitional care in the recent decades, often described as re-institutionalization (Priebe et al. 2005). There has been growing concern about the lack of equitable distribution of state resources to take care of a marginalized group of people living in isolated communities (Solomon and Davis 1985). Moreover, the burden on the caregivers or family members of the mentally ill has been largely ignored (Saxena et al. 2007). The partial success of deinstitutionalization, therefore, raises several critical questions on its timing. Was the origin of deinstitutionalization the result of ideological changes or the result of fiscal crisis and expansion of the welfare state (Lerman 1982)? Another hypothesis has been that psychoactive drugs in hospitals in the 1950s have been the driving force behind deinstitutionalization (Lyons 1984). Therefore, the present article examines the role of the advent of effective pharmacological treatments on the evolution of deinstitutionalization.

The introduction of tranquillizers

In 1954, Kline and French Labs, an American company, received the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for its tranquillizing drug, chlorpromazine, under the trade name Thorazine (Judith 1974). The chlorpromazine was soon followed by other newly-synthesized psychotropics, including reserpine, with a remarkable ability to control the behaviour of most dangerous or disturbed patients. The reception of such drugs by the hospitals with heavy enthusiasm led the drug companies to put pressure on state legislatures further to promote the administration of psychoactive drugs to hospital inmates. Several conferences were organized to educate policymakers and hospital administrators on the beneficial effect of drugs, even in the most severely ill patients. These effects often resulted in acceptable social behaviour in chronically ill patients, compared to traditional modes of care and therapy in the mentally ill such as electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomy and insulin shock, which could not be used outside the hospital environment. A medical revolution was observed with entire psychiatric wards transformed in a matter of weeks with patients undergoing a metamorphosis from combative to cheerful persons. Such changes also had a marked impact on the attitudes of highly stressed hospital staff as patients became more compliant and could now be involved in additional activities (Emmet and Wilkinson 1995). These drugs were soon perceived for their possible use in the community setting.

The effect of treatment on discharge rate

Several studies had after that attempted to explore the influence of the introduction of psychoactive drugs on discharge rates in mental hospitals, often showing conflicting findings. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) study showed an essential role of tranquillizers in providing the reliance on the community for the care of the mentally ill. The tranquillizers not only lowered the need for hospitalization but also enabled the early release of patients from hospitals (Pasamanick, Frank, and D 1967).

Several retrospective studies conducted in the 1980s in the U.S., mainly involving the states of Michigan and California, on the contrary, demonstrated that drugs did not influence the discharge rates (Joseph 1982). The studies showed that release rates of untreated patients were, in fact, lower than those who were treated. Furthermore, the decrease in inpatient populations was attributed to extensive implementation of federal health and welfare programs in the early1960s (Lerman 1982; Aviram, Syme, and Cohen 1976; Shadish and Bootzin 1981).

The drugs were suddenly given credit for upward trends seen in discharge rates, although the phenomenon of increase in discharge trends was seen before introducing psychoactive drugs. The industry oversold the drugs for profiteering, and politicians benefited by giving bold speeches in favour of the pharma industry, creating a sense of belief that the availability of new drugs had created an environment conducible to implement deinstitutionalization (Lyons 1984). Families of mentally ill patients developed a greater tolerance and readiness to absorb their relatives back into the communities.

Predrug vs Postdrug period

It is further believed that serious efforts towards large scale discharge from mental hospitals started much before in the 1930s, when Dr John Grimes, under the aides of the American Medical Association (AMA), conducted a two-year-long study on the condition of mentally ill patients in mental hospitals (Grimes 1934). Grimes proposed the idea of deinstitutionalization and stressed the need of bringing in social workers to allow the parole of thousands of mentally ill. He also emphasized that such an approach would eventually free up resources for a more focused approach to acute cases in hospitals, thereby reducing their likelihood of becoming chronic.

It has also been observed that discharge rates have, in fact, started declining in mental hospitals even before the introduction of psychotropic drugs (Earl et al. 1959). The study by Gronfein et al. compared the discharge rates in U.S. mental hospitals in the period from 1946 to 1954 (also termed as a predrug period) with the period from 1955 to 1963 (also termed as a postdrug period) (Gronfein 1985). The author demonstrated that the mean increase in the discharge rate per state was 8.2% lower in the postdrug period than the predrug period. Thus, the study demonstrated that continued discharge of patients from hospitals was more of an extension of a pre-existing trend before introducing treatment (Gronfein 1985). Similar patterns were observed in other parts of the world, including England and France, with a decline in inpatient populations long before introducing drugs (Brown et al. 1966).

It has also been hypothesized that studies examining the effect of drugs on deinstitutionalization often failed to account for data on readmission. If patients continue to be readmitted after their discharge to the community, the policy of deinstitutionalization may have failed to meet its objective (Johnson 1990). Most recently, a study by Pow et al., which examined the U.S. census data from the period of 1935 to 1964, showed that although there was a substantial increase of up to 127% in discharge rate from 1954 to 1961, there was only 1% increase in the hospital population during the period (Pow et al. 2015). The authors of the study reasoned that during the study period, a significant increase of first admissions (23%) and readmissions (117%) were observed.

Conclusion

The influence of pharmacological treatments on changes in governmental policies in the implementation of deinstitutionalization resulted from its introduction into the already favourable environmental conditions. Instead, it was an influence of an emergence of an alternate philosophy and desire of the society towards finding an alternate, more humanly mode of treatment of mentally ill patients. One of the primary explanations for this observation was a slow rate of deinstitutionalization; immediately after introducing psychotropic drugs in 1955, deinstitutionalization gathered momentum after the emergence of civil movements favouring better admission and reform procedures in the 1970s. Furthermore, failure to account for readmissions rates, which increased at an equal rate as discharge rates, gave a false perception of drugs being the driving force behind deinstitutionalization. In summary, the drugs alone could have little impact on the revolutionary exodus of patients from hospitals to community-based settings. Although deinstitutionalisation policy remarkably improved the quality of life of thousands of mentally ill patients, considerable work still needs to be done to provide adequate support and resources to the community.

References

Arnhoff, F. N. 1975. “Social consequences of policy toward mental illness.” Science 188 (4195): 1277-81. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1145195.

Aviram, U., S. L. Syme, and J. B. Cohen. 1976. “The effects of policies and programs on reduction of mental hospitalization.” Soc Sci Med 10 (11-12): 571-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-7856(76)90027-5.

Becker, I., and J. L. Vázquez-Barquero. 2001. “The European perspective of psychiatric reform.” Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl (410): 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.1040s2008.x.

Brown, George W. , Bone Margaret, Dalison Bridget, and K. Wing John. 1966. Schizophrenia and Social Care. London: Oxford University Press.

Chow, W. S., and S. Priebe. 2013. “Understanding psychiatric institutionalization: a conceptual review.” BMC Psychiatry 13: 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-13-169.

Earl, P, HP Person, MB Kramer, and H Goldstein. 1959. Patterns of Retention, Release, and Death of First Admissions to State Mental Hospitals. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office.: DHEW Public Health Monograph No. 38.

Emmet, LB., and WE Wilkinson. 1995. In Pharmacologic Products Recently Introduced in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders, 63-72. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Goffman, E. 1961. Asylums; essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Garden City: Anchor Books.

Goldman, H. H., N. H. Adams, and C. A. Taube. 1983. “Deinstitutionalization: the data demythologized.” Hosp Community Psychiatry 34 (2): 129-34. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.34.2.129.

Grimes, J.M. 1934. Institutional care of mental patients in the United States. Chicago.

Grob, G. N. 1983. “Historical origins of deinstitutionalization.” New Dir Ment Health Serv (17): 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23319831704.

Gronfein, W. 1985. “Psychotropic Drugs and the Origins of Deinstitutionalization.” Social Problems 32 (5): 18.

Johnson, A.B. 1990. Out of bedlam: the truth about deinstitutionalization. New York: Basic.

Joseph, M. 1982. “Deinstitutionalizing the mentally ill: processes, outcomes, and new directions.” In Deviance and Mental Illness, 147-76. Beverely Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Judith, S. 1974. Chlorpromazine in Psychiatry. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Kramer, M. 1977. Psychiatric Services and the Changing Institutional Scene: 1950-1985. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.: DHEW Publication No. (ADM) 77-433.

Lerman, P. 1982. Deinstitutionalization and the Welfare State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lyons, Richard D. 1984. “How release of mental patients began.” New York Times, October 30, 1984.

McCulloch, A., M. Muijen, and H. Harper. 2000. “New developments in mental health policy in the United Kingdom.” Int J Law Psychiatry 23 (3-4): 261-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-2527(00)00038-8.

Pasamanick, B, S Frank, and Simon D. 1967. Schizophrenics in the Community. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Pow, J. L., A. A. Baumeister, M. F. Hawkins, A. S. Cohen, and J. C. Garand. 2015. “Deinstitutionalization of American public hospitals for the mentally ill before and after the introduction of antipsychotic medications.” Harv Rev Psychiatry 23 (3): 176-87. https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000046.

Priebe, S., A. Badesconyi, A. Fioritti, L. Hansson, R. Kilian, F. Torres-Gonzales, T. Turner, and D. Wiersma. 2005. “Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison of data on service provision from six European countries.” Bmj 330 (7483): 123-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38296.611215.AE.

Priebe, S., K. Hoffmann, M. Isermann, and W. Kaiser. 2002. “Do long-term hospitalised patients benefit from discharge into the community?” Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37 (8): 387-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0568-1.

Saxena, S., G. Thornicroft, M. Knapp, and H. Whiteford. 2007. “Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency.” Lancet 370 (9590): 878-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61239-2.

Segal, S. P., and E. W. Moyles. 1979. “Management Style and Institutional Dependency in Sheltered Care.” Soc Psychiatry 14 (4): 159-165.

Shadish, W. R., Jr., and R. R. Bootzin. 1981. “Nursing homes and chronic mental patients.” Schizophr Bull 7 (3): 488-98. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/7.3.488.

Solomon, P., and J. Davis. 1985. “Meeting community service needs of discharged psychiatric patients.” Psychiatr Q 57 (1): 11-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01064972.

Leave a Reply